An Introduction to Nazrul’s Prose

Subrata Kumar Das

The National poet of Bangladesh Kazi Nazrul Islam (1899-1976), popularly known as

Vidrohi Kobi(The Rebel Poet), was no less creative in his prose. He wrote nineteen short stories,

three novels and five books of essays. Alongwith those we have got a good number of speeches

by him that he delivered on different occasions and a total of seventy seven letters that he wrote

to different people. In all these prose works Nazrul has proved his genius regarding their forms

and contents. As his poetry does, his prose also exposes his rebellious attitude and protest against

the established values and customs. His belief in the freedom of India, progressivism, liberalism,

women’s liberation and communal harmony has beendelineated scatteredly through all his prose

works.

Essays

The articles that Nazrul considered as his essays were mostly published in the early twenties

of the twentieth century. Then hewas closely associated with the newspapers and periodicals like

Novojug(The New Era), Dhumketu (The Comet) and Gonovani (The Voice of the People). The

articles published in the editorial columnare later on included and published titled Jugovani(The

Voice of the Era), Rudromongol(The Violent Good) and Durdiner Jatri (The Traveler through

Calamity). The book Rajbondir Jobanbondi(Deposition by a Political Prisoner) which he wrote

during his prison-days against the ill treatment towards the prisoners by the authority is also

considered as a book of this genre. The last book of essay by Nazrul is Dhumketu(The Comet)

that was published much later after the poet’s inactivity due to illness.

Jugovani was published in October 1922. The articles of the book are: Novojug(The New

Era), “Geche Desh Dukkha Nai, Abar Tora Manush H’a”(No Pain for the Lost Motherland, Let

You be Human Again), Dyerer Smritistambho(The Monument for Dyer), Dhormoghot(Strike),

Lokmanyo Tiloker Mrityute Bedanatur Kalikatar Drishya(The Sorrowful Calcutta at the Death of

Lokmanya Tilak), Muhazirin Hatyar Janyo Dayi Ke(Who is Responsible for the Death of

Muslims), Bangla Sahitye Musolman(Muslims in Bengali Literature), Chhutmarga (Prejudice

about Touch), Amader Sokti Sthayi Hoi Na Keno(Why Doesn’t Our Power Last Long), Kala

Admike Guli Mara(To Shoot a Black), Shyam Rakhi Na Kool Rakhi(Between the Horns of a

Dilemma), Lat-Premik Ali Imam (Aali Imam ⎯the Lat-lover), Bhab O Kaz(Idea and Action),

Satyo-Shiksha(The Education of Truth), Jatiyo Shiksha(National Education), Jatiyo

Bishwobidyalaya(The National University) and Jagoroni(Awakening). The last essay Jagaroni had a different title Udbodhon (Inauguration) while it was published in the periodicals. Since

these were the newspaper articles, they took the touch of current affairs in them. The essays of

Jugvaniwere compact with ideas concerning the ill-treatment, exploitation and injustice by the

British Government during the non-cooperation and Khilafot movement. It was the first book by

Nazrul that was banned.

The next volume of essays by Nazrul is Durdiner Jatri(The Traveler through Calamity)

which was published in book form in 1926. The book comprises seven essays, all of which were

published as the editorials of Dhumketu,the bi-weekly, edited by Kazi Nazrul Islam himself. The

essays are: Amar Lakshmi-Chharar Dol(My Naughty Darlings), Tubri Banshir Dak(The Call of

the Snake-Charmer’s Flute), Mora Sobai Swadhin, Mora Sobai Raja(We All Are Free, We All

Are Kings), Swagata(Welcome), Mai Bungkha Hu(I am Hungry), Pothik, Tumi Poth

Haraiachho(Pedestrian, You Have Lost Your Way) and Ami Soinik(I Am a Soldier)

The third collection of essays Rudromongol(The Violent Good) was published in Calcutta in

the year 1927. There were eight essays in this book among which six were published in Dhumket.

Those six are the title-essay Rudromongolitself, Amar Poth,(My Way), Mohorrom(An Incident

in the History of Islam), Bishovani(The Venom Message), Kshudiramer Ma(Mother of

Kshudiram) and Dhumketur Poth(The Way of Dhumketu). The rest two essays Mondir O Mosjid

(Temples and Mosques) and Hindu-Musolman(Hindus and Muslims) were published in

Gonovani.One can easily detect the rebellious attitude of Kazi Nazrul Islam in the essays of

Durdiner Jatriand Rudromongol.

When Dhumketu,the last collection of essays by Nazrul, was published in 1960 it was a

compilation. It had twenty one articles: Dhumketur Adi Udoy Smriti (Remembrance of the

Inauguration of Dhumketu), Dhumketur Poth (The Way of Dhumketu), Amar Dhormo (My

Religion), Mohorrom (About the Muslim Occasion), Mushkil (Problems),Lanchhita (The

Violated), Bishovani (The Venom Message),Nishan-Bordar (The Flag-Bearer), Tomar Pon Ki

(What’s Your Resolution), Viksha Dao (Give Me Alms), Ami Soinik (I Am a Soldier), Bortoman

Bishwosahityo (Contemporary World-Literature), Mai Bukha Hu ( I am Hungry), Kemal (About

the Great Hero of Turkey), Bayerthotar Byatha (The Pain of Failure), Amar Sundor (My Beauty),

Bhabbar Kotha (What’s to be Thought),Aj Ki Chai (What I Want Today), Nazrul Islamer Potro

(A Letter from Nazrul Islam), Ekkhani Potro [Ibrahim Khan] (A Letter [Ibrahim Khan]) and

Chithir Uttarey (In Response to a Letter). Among them Ekkhani Chithi is written by Principal

Ibrahim Khan to Nazrul. Some of the essays of this book were borrowed from his earlier

collections of essays.

Nazrul’s Rajbondir Jobanbondi has a distinct characteristic unlike the above ones. This

deposition was delivered by Nazrul on 16 January, 1923 when he was sentenced one year’s

rigorous punishment on charge of sedition. It isknown that on 7 January 1923, Sunday afternoon,

he wrote this deposition while awaiting trial in the Presidency Jail, Calcutta. Rajbondir

Jobanbondiwas published in Dhumketuon 27 January 1923. It is worthy to mention that in the

Nazrul Rochonabali (Works of Nazrul) in four volumes by the Bangla Academy, Dhaka, the

essays by Kazi Nazrul Islam have been organized into two volumes ⎯in Vol-1 Jugvani,

Rajbondir Jobanbondi, Durdiner Jatriand Rudromongoland in Vol-4 Probondho(Essays).

Under the last title all the names of essays previously mentioned in connection to Dhumketuhave

not been included as some of them were placed in his earlier collection of essays. The other

essays that were not included in his essay-books are Turk Mohilar Ghomta Khola(Opening the Veil of a Turkish Women), Barsharombhe(At the Beginning of the Rains), Sotyobanee (The

Massage of Truth), and Dhormo O Karmo(Religion and Duty). Except those very significant

essays there are a comparatively less significant ones also. Nine reviews on books by

contemporary writers have been incorporated under the title Sahityo Porichiti(Introduction to

Literature).

These short articles are: Ainar Freme(‘The Frame of the Mirror’, about the storybook ‘Aina’by Abul Monsur Ahmed), Haramoni (‘The Lost Games’ about the folkcollection by Muhammed Mansur Uddin), Bondir Banshi(‘The Flute of the Captive’

about the poetry book by Benazir Ahmed), Dilruba(‘The Sweetheart’ about the poetry by

Abdul Kadir), Agamibare Samapyo(‘To Be Finished Tomorrow’ about a novel by

Mohammad Kasem), Shekwa O Jawabe Shekwa(a review on the translation of the

famous book of great poet Iqbal by Mohammad Sultan), Sanjher Maya(‘The Attraction

of the Dusk’ about Begum Sufia Kakal’s poetry book), Poth-Harar Poth(‘The Way of

the Stray’ by Sree Barada Charan Majumder) and Sujoner Gan(‘Songs of Sujan’ about

the song-book by Girin Chakrabarti). In the book there are some more articles:

Langol(‘The Plough’ first published in the special issue of its first year in Langolwhich

was published on 16 December 1925. The Chief Director of the weekly was Kazi Nazrul

Islam himself); Political Tubribazee (‘Volubility in Politics’ was published in ‘Langol’in

its third issue); ‘Gonovani’ O Muzaffar Ahmad(“The Voice of the People’ and Muzaffar

Ahmad’, published in the weekly Atmoshoktior The Power of Soul in August 1926. This

is actually a letter written to the editor of Atmoshakti as a reaction of an article published

in the same weekly on 20 August of the same year which criticized the role of Gonovani.

This has been included in Nazruler Potrovoli[Letters of Nazrul, ‘Nazrul Institute, Dhaka,

1995]);Bangaleer Bangla(Bangla of the Bengalees, published in the daily Novojug[The

New Era in April 1942]); and Sur O Sruti(Melody and Hearing, anincomplete article

was published in Nazrul Geeti Anweshaor ‘In Search of Nazrul Songs’ edited by Sree

Kalpataru Sengupta from National Book Private Agency Ltd, Calcutta. It is assumed that

Kazi Nazrul Islam began to write it in 1935-36). Along with this one we have got some

more articles on music and its melody in the book, which are Mia Ka Sareng, Duti

Ragini, Hosenee Kanadaand Neelamboree.The other essays are Amar League-Congress,

Novojuger Sadhona, Sromik Proja Sworaj Somprodayer Gathon Pronaliand Ekti Rupok

Rachonar Khosra Porikolpona.Under the title Chanachur (Tit-bits) there are eight

humorous features which had been published in the weekly Saogat.The features are:

Domni Status, Punarmushiko Bhabo, Chaturbargo-Pholer Bonta, Bibaho Ain Bill,

Chardik Theke Pagla Tore Gheira Dhoreche Pape, “Hai Janti Paro Na”, Fall in (Love

Noi) War andDhone Prane Mara Jai.The last item of the part Probondhois also a

humorous ⎯ one Huq Saheber Hashir Golpo(Humorous stories by Huq Shaheb) which

was published in the daily Novojug on 14 Jayistha1349 B.S. In this connection it may be

mentioned that the essay Nazrul Islamer Potrowhich was included in the book Dhumketu

is placed in the Abhibhashon (Speeches) chapter here under the title Krishak Sromiker

Proti Sambhashon.The three translated articles by Nazrul which have been included in

the book are Jononider Proti(To Mothers), Poshur Khutinati Bisheswotwa(The Specific

Characteristics of Animals) and Jibon-Bijnan (Life-Science). These articles were

published in Bongiyo Musolman Sahityo Potrika (Boishakh,1329 B.S) translated from

the original of the magazine section of ‘The Englishman’.

Letters

We have by now got only seventy seven letterswritten by Kazi Nazrul Islam, though it can

be easily assumed that he wrote many other letters that are yet to be discovered. Most of his

letters are about his personal affairs, but there are some that expose Nazrul’s different approaches

and philosophies more sharply. Some letters by him show the turns of love that we observe in his

life. Regarding the discussion about Nazrul’s letterswe have taken mostly into consideration the

book Nazruler Potravoli(Letters of Nazrul, Ed. Shahabuddin Ahmad, Nazrul Institute, Dhaka,

1995).

The first letter, as we know Nazrul wrote, was to his former school teacher Maulvi Abdul

Gafur. Written on July 23,1917 from Moslem Hostel, Raniganj this first one shows ‘Nazrul

Eslam’ in the signature. In this letter Nazrul frequently used Arabic and Urdu words.

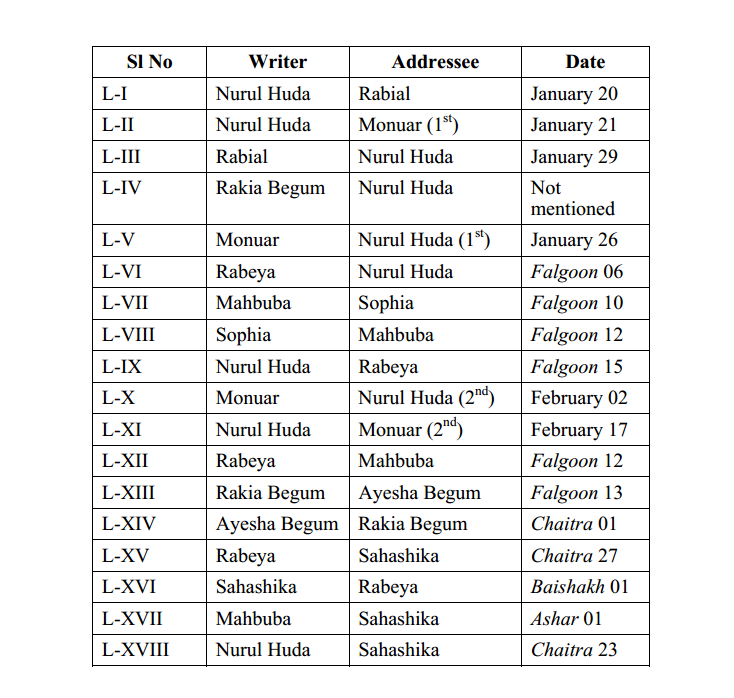

The letters of Nazrul are as follows:

It is true most of Nazrul’s letters are not very worthy in respect of his literary works ⎯ rather

most of them expose his familial and personal issues. Even then we should not deny the

importance of some of them. For example if we consider Nazrul’s letter to Principal Ibrahim

Khan (included in this book) we can realize the role of his letters in the field of his literary

activities. Similarly letters of serial numbers 20, 22, 37, 38, 39, 40, 41, 42, 44, 61, 74 are more

important regarding Nazrul’s ideological and intellectual turns.

If we look at the years of the writing of these letters, we will see that Nazrul wrote the highest

number of them in 1926, 1927 and in 1928. In 1926 he wrote 13 letters, in 1927 and 1928 9

letters each, in 1942 and 1925 6 letters each, in 1920, 1933 and 1938 4 letters each, in 1929, 1935

and 1940 3 letters each, in 1921,1932 and 1937 2 letters each. In the years 1917, 1919, 1922,

1930, 1941 he wrote the least number of letters ⎯ only one in every year. At least in five years of

his life, no letter of Nazrul is yet found. The year 1918 may be overlooked, but what about 1923,

1924, 1931, 1934, 1939? The other point, which may arouse interest in this regard, is that his first

novel Bondhonhara(Free from Bonds, published serially in 1920 and 1921) is an epistolary one.

From this it may be noticed that from his early years of literary career he was a good writer of

letters.

Speeches

If we look at the speeches by Kazi Nazrul Islam we will see that the number is only fourteen

which does not comply with the activities of the poet’s life. Because throughout the whole

twenties Nazrul was involved directly in politics till his full alienation from outer life and absorption in music around the year 1930. But from the dates of his speeches we may reach to the

conclusion that we have not yet gotthat much speech before 1930.

Now we will try to make a possible chronologicallist of his speeches that he delivered in

different political and literary ceremonials. It is worthy to keep in mind that none of Nazrul’s

speeches was completely of partisan politics. Rather the contents were always regarding literary

aspects and general socio-political issues.

The first speech by Nazrul that we have yet got in hand is Krishok Sromiker Proti

Sombhashon(A Speech to the Farmers and Labourer). Thisis the only speech that Nazrul himself

could not deliver. In Nazruler Potravoli(‘Letters of Nazrul’ edited by Shahabuddin Ahmed and

published by Nazrul Institute, Dhaka) this speechhas been included as a letter (sl no – 16). On 17

and 18 January of 1926, the convention of Mymensing District Krishok O Sromik Sommelon was

arranged in the town of Mymensing. Nazrul wrote this speech on that occasion. Noted proletariat

leader Hemanta Kumar Sarkar readthe speech out in the convention. It was later on published in

Langol(The Plough) in its 5th number, 1st volume (7 Magh, 1332 B.S). In this connection it may

be mentioned that around the year 1926 Nazrulattended some more meetings and conferences

with Hemanta Kumar Sarker. In Magh1926 Nazrul participated in the conference of the

Fishermen’s organization in Madaripur in June and in Dhaka and Chittagong respectively in July

of the same year. In all these conferences he was accompanied by Hemanta Kumar Sarkar. But

none of those speeches that Nazrul delivered is yet available.

Around these years Nazrul gradually exposed himself as a political personality and

consequently began to attend different meetings. He visited Faridpur in 1925 to attend the

Pradeshik Sommelon of Bongiyo Congress, and in 1926 Feni, Jessore, Khulna, Begerhat,

Daulatpur, and Sylhet to attend a Congress meeting.In the same year he participated in the

election of the Upper House of Indian Central Legislative Assembly from Dhaka. Moreover in

February 1927 he attended the Ist yearly meeting of Muslim Sahityo Somaj (Literary Society of

the Muslims) and after just one year the 2nd yearly meeting of the same organization. We know

on 15 December 1929, Nazrul was accorded a national reception by the whole Bangalee nation.

Before that he visited every part and corner of the country. In 1928 he traveled Sylhet, Rangpur,

Rajshahi and in 1929 Thakurgaon, Sandwip, Kushtia, Bogra and the description of his travel

arouses the question related to the number ofhis speeches. Only two speeches delivered in

Chittagong are available.

In January 1929 Nazrul was honoured by the Chittagong Bulbul Society. In response to the

welcome speech, he delivered the speech Protinomoskar (Speech of Thanks). In the same month

he presided over the anniversary ceremony ofChittagong Education Society founded by Abdul

Aziz where the title of his speech was Muslim Sonskritir Chorcha(Practice of Muslim Culture).

Both Protinomoskarand Muslim Sonskskritir Chorcha were published in Bulbulin BoishakhAshar 1341 B.S and in Falgoon 1343 B.S. respectively.

After this in December 1929 Nazrul got the national recognition ceremonially. The

organisers had to overcome many disruptions. On 15 December, the poet was taken to Albert Hall

at a floral procession. At the beginning of the ceremony famous song-star Sree Umapada

Bhattacharjy sang the popular song of Nazrul’s Chol Chol Chol(Quick, Quick, Quick March).

The first few lines of the song are:

Quick, Quick, Quick March!

Up in the sky trumpet rolls,

Below the valley of Earth overflows,

Ye Youths of Golden Dawn!

A-head, A-head, A-head,

Quick, Quick, Quick March!

(Tr. Abdul Hakim, Poetry of Kazi Nazrul Islamin English translation, Edited by Mohammad

Nurul Huda, Nazrul Institute, Dhaka, 1997, P-489).

Acharya Prafulla Chandra Ray who presided over the Reception Ceremony told in his speech:

…In modern literature we find the existence of originality only in two poets. They are

Satyendranath Datta and Nazrul Islam. Nazrul is a poet, a talented original poet. His talent has not

been nourished in the atmosphere of Tagore writings. So Rabindranath Tagore has recognised him

as a poet. Today I am enormously glad to think that Nazrul Islam is not the poet of the Muslim, he

is the poet of Bengali people…. Today people irrespective of community and religion are paying

respects to Kazi Nazrul Islam….

(Tr. Karunamaya Goswami Kazi Nazrul Islam: A Biography, Nazrul Institute, Dhaka, 1996, P-107).

Nazrul delivered his Protibhashon(The Acknowledgement Speech) after S. Wazed Ali,

President of Nazrul Reception Committee, read out the address of welcome.

After this national reception wherever Nazrul visited, he was given a warm welcome. In the

year 1932 he attended the Bongiyo Muslim Torun Sommelon(Conference of Bengal Muslim

Youths) at Sirajganj. Regarding this visit Karunnamaya Goswami writes:

…The renowned singer Abbassuddin Ahmad accompanied Nazrul to Sirajganj from Calcutta.

The train carrying Nazrul Islam and Abbasuddin Ahmad reached Sirajganj railway station in the

cold morning of the 5th November. A large number of people went to the station to receive the

poet wherefrom he was brought to the town in a large procession….

(Karunamaya Goswami, ibid, P-122)

The title of Nazrul’s speech is Toruner Sadhona(The Practic of the Youth). A part of this

speech was later on published under the title Jouvaner Gan(The Song of the Youth). In the

second day’s session Nazrul only recited the poem Nari(Women) and performed some songs.

In 1936 Nazrul visited Faridpur for the second time (or, third time?). As the president of the

District Muslim Students Conference he presented the speech Banglar Muslimke Banchao(Save

the Bengali Muslims).

The next speech that we get by Nazrul is Jono-Sahityo(People’s Literature). In 1938 Nazrul

delivered this speech in the inauguration ceremony of the Jono-Sahityo Somsod(Society for

People’s Literature). In the office of the daily Krishok(The Farmer) in Calcutta Nazrul told:

…The purpose of people’s literature is to create an issue for people and portray their

sentiment. Now-a-days communalism has been an acute problem for the people. Its solution also

forms an aspect of people’s literature. The periodicals and their editorials could do no good. The

editorial opinions sound like hailstorm of advice from the top. It cannot influence the public

opinion and the popular view are not created….

(Karunamaya Goswami, ibid, P-145)

About Krishokand Jono-SahityoKhan Mohammad Moinuddin says:

In November, 1939 [or 1938?] there appeared in Calcutta a daily named Krishok.The cause

behind its appearance was to create political consciousness among the huge agrarian people.

Prof.Humayun Kabir, Dr. Sirajuddin Ahmed, Kazi Mohammad Idris, Mohammad Hasan Ali were

closely associated with the daily. Abul Mansoor Ahmed was the chief editor of it.

Taking Krishokat its centre, an organization named Jano-Sahityo-Somsodwas founded….

In one of its addasHumayun Kabir tabled up the question ‘what is people’s literature?…

The poet said, ‘People’s literature is that which causes movement in the minds of the common

folk. Its language must be very easy avoiding all ornamentation that everyone can understand that

literature…? (Translation)

Jono Sahityowas published in Noya Jomana(The New World) in its Falgoon1345 B.S (vol. 01,

number 04) issue.

Nazrul’s next speech is Ustad Jamiruddin Khan.Ustad Jamiruddin Khan was a veteran

maestro of the tweenties and thirties. In 1929 when Nazrul came to Calcutta he took instruction in

music from this maestro of classical music. Nazrul dedicated his book of songs Bonogeeti (Songs

of the Garden), first published in 1932 to Ustad Jamiruddin Khan. Ustad died on 26 November

1939. On December 10, a condolence meeting was arranged where Nazrul, the president of the

meeting, delivered the speech.

Nazrul’s speech Swadhinchittotar Jagoron(Awakening of the New Spirit) was delivered as

the president of the Eid Reunion of Bengal MuslimLiterary Society. Before the reunion, held in

1940, Nazrul’s mental distress had already started. In his speech he said:

…We will have to give up timidity, weakness and cowardice. We will live with our just claim

of right, not with a begging bowl. we will bend low our head to none. We will mend shoes on

streets and live our lives with labour but we will not want anyone to take pity on us. I want to see

the Muslim youth of Bengal to reflect this idea of freedom in their lives. This is the teaching of

Islam. I want everyone to learn this lesson. This has been the lesson of my life. I have accepted

sorrows and shocks with smile but never made the degradation of my soul. I have never sacrificed

the spirit of my self-independence. “Proclaim O hero, eternally high is my head” is a song, which I

have sung out of this spirit. I want to see the birth of such liberated souls. This is the greatest

massage of Islam.

(Tr. Karunamaya Goswami, ibid, P-148)

Shirajiis the smallest speech that Nazrul gave on the occasion of the inauguration of Siraji

Public Library and Free Reading Room at 2/1 European Asylam Lane, Calcutta. On 22 March

1940 the library was opened for public at 5 in the afternoon and Nazrul attended the function as

the president. Nazrul’s tribute to Syed Ismail Hussain Siraji (1880-1931), a noted writer of the

Muslim Bengal, has been exposed in the speech. The speech was published in the daily Krishok

on 9 Choitro, 1347 B.S.

Nazrul’s next speech is Allahar Pothe Atmosomorpon(Surrender to the Ways of God) which

was published in the daily Krishok (8 Pous, 1347 B.S). This speech was delivered on 23

December, 1940 (7 Pous, 1347 B.S) at the conference room ofCalcutta Muslim Institute. Nazrul

spoke on the second day’s session of Calcutta Muslim Students Conference.

On 16 March 1942 Nazrul addressed his last but one in Fourth Yearly Conference of

Bongaon Sahityo Sobha. To understand Nazrul’s mystic philosophy this address Modhurom

(Delightful) is much more significant. On request from the sub-division magistrate Mizanur

Rahman, Nazrul agreed to preside over the conference. Ajharuddin Khan informs:

Nazrul did not want to attend the Bongaon Literary Conference. Then he had innumerable debtors

for whom he became exhausted. On the other hand he lost every thing for the medication of his

diseased wife. He had to pay small loans for which he paid high interests. To pay the small loans

and for the expenses of his wife’s treatment he took four thousand taka from the solicitor of

Calcutta Ashim Krsna Datta mortgaging the royalty of the records. The condition was that till the

repayment of the loan he would take the royalties from the gramophone companies. Nazrul earned

the highest sum of money in the thirties but in the same decade he sold his ownership of his books

and borrowed an amount of tk. four thousand on interest. In respect of financial terms his life

came to a closure. If the meals of one time are somehow managed, the thought of the next time

expands its claws. The then subdivisional magistrate Mizanur Rahman took the chance in the

poverty-stricken condition of the poet.(Translation)

(Bangla Sahitye Nazrulor Nazrul in Bangla Literature, First Supreme Edition, Calcutta 1997, P-205)

And the truth is Nazrul did not get the previously settled money. In such a sad and distressed

condition Nazrul delivered his last Jodi Ar Banshi Na Baze (If the Flute Blows No More) in the

next month. On 5 and 6 April 1941, the Silver Jubilee of Bongiyo Musolman Sahityo Somity was

organized in the Muslim Institute, Calcutta. Nazrul addressed as the president there.

It is true, in his essays, letters and speeches Nazrul repeated his ideas and thoughts frequently

but to evaluate the philosophical turns in Nazrul’s life his non-fictional prose works are no less

significant. Though his non-fictional prose-works are burdened with sentiments and

ornamentation, they express Nazrul’s poetic merit more without hampering the intellectual

development that is very necessary for prose-pieces.

Yet, we must appreciate his prose that display Nazrul’s mental bent, his theories of literature

and his thoughts regarding socio-political condition of the country.

To email Subrata Kumar Das: subratakdas@yahoo.com